A recent Pew Research Center study showed that Americans are growing increasingly less religious, opting to identify as “Spiritual But Not Religious,” rather than maintaining a single religious ideology. In just 5 years, the percent of U.S. adults identifying as such has grown 8 percentage points, up from 19% to 27% of the population as a whole. Conversely, those who identify as ‘religious’ have dropped significantly, down 11 percent since 2012. What accounts for these changes? Are Americans simply being lazy with their faith adherence, or are they making a conscious choice to move away from religion and towards spirituality?

To some degree, the answer depends on who is asked. The Catholic website Aleteia weighs in on those who are “Spiritual But Not Religious” (SBNR) as ineffectual cherry-pickers: “Most moderns who say they have faith in everything mean to say they have faith in nothing.” They argue against selective adherence to a variety of faith traditions by using the metaphor of a paint-box: “All the colors mixed together in purity ought to make a perfect white. Mixed together on any human paint-box, they make a thing like mud, and a thing very like many new religions. Such a blend is often something much worse than any one creed taken separately…”

Another common argument against being ‘Spiritual But Not Religious’ is that it does not provide a useful ritualistic framework. SBNR critics claim humans need ritual, and that ritual exists for a reason: “…as creed and mythology produce this gross and vigorous life, so in its turn this gross and vigorous life will always produce creed and mythology.” (From “Heretics,” by Gilbert Chesterton)

Criticism of SBNR beliefs is not limited to the right, either. A recent article in Psychology Today offers, “Spirituality sometimes goes with a set of practices that may be reassuring and possibly healthy. Activities such as yoga and tai chi are good forms of exercise that make sense independent of any spiritual justification. (But) Sometimes spirituality fits with rejection of modern medicine, which despite its limitations is far more likely to cure people than weird ideas about quantum healing and ineffable mind-body interactions. Evidence-based medicine is better than fuzzy wishful thinking.”

If being ‘Spiritual But Not Religious’ leads one to a colorless existence void of necessary ritual and at risk of fuzzy thinking, why would anyone choose this self-identifier?

In an article on decreasing Millennial religiosity, one journalist proffers that capitalism is to blame: “Spirituality is what consumer capitalism does to religion. Consumer capitalism is driven by choice. You choose the things that you consume – the bands you like, the books you read, the clothes you wear – and these become part of your identity construction. Huge parts of our social interactions center on these things and advertising has told millennials, from birth, that these are things that matter, that will give you fulfillment and satisfaction. This is quite different from agricultural or industrial capitalism, where someone’s primary identity was as a producer. The millennial approach to spirituality seems to be about choosing and consuming different “religious products” – meditation, or prayer, or yoga, or a belief in heaven – rather than belonging to an organized congregation. I believe this decline in religious affiliation is directly related to the influence of consumer capitalism.”

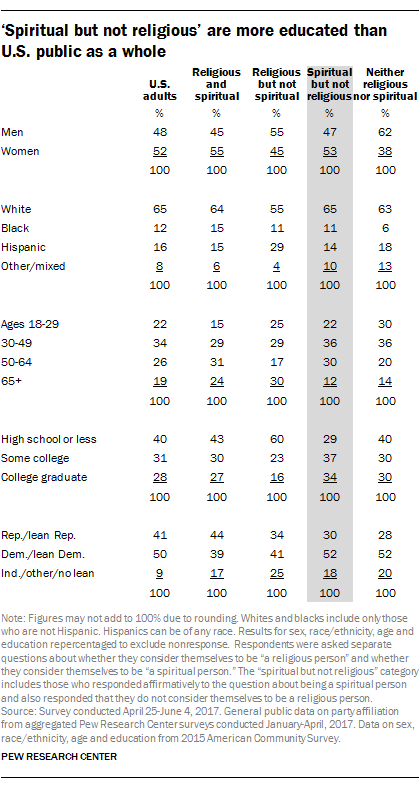

All of these reasons for the increase in spirituality over religiosity may be true. But there may be a simpler explanation: According to the aforementioned Pew Report, “Spiritual but not religious” Americans are more highly educated than the general public. Seven-in-ten (71%) have attended at least some college, including a third (34%) with college degrees.

Numerous articles have documented the challenge that the Internet represents to established authorities. Education, then (especially access to knowledge via the Internet), may be leading to increased questioning of authoritative institutions, including religious organizations. While the move towards ‘Spiritual But Not Religious’ attitudes could be caused by some form of intellectual laziness, the arguments for this are largely anecdotal. Occam’s Razor teaches us that the reasoning or hypothesis requiring the fewest assumptions is usually the right one. Given the rise in those who identify as ‘Spiritual But Not Religious’ is statistically and positively correlated to education, awareness is the most likely cause for the move away from religion.

No comments yet.