“The multitude always strains after rarities and exceptions, and thinks little of the gifts of nature; so that, when prophecy is talked of, ordinary knowledge is not supposed to be included. Nevertheless it has as much right as any other to be called Divine.”

— Baruch Spinoza

Theologian Anselm of Canterbury defined God as, “that than which nothing greater can be conceived.” Philosopher Baruch Spinoza carried this idea to its logical extreme:

“By God I understand a being absolutely infinite, i.e., a substance consisting of infinite attributes, of which each one expresses an eternal and infinite essence.”

Physicist Albert Einstein agreed with this definition, stating,

“I believe in Spinoza’s God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists.”

The word God is an abstract expression which anybody can incorporate into language. It is, “not the exclusive property of any one tradition,” according to religious historian Karen Armstrong’s interpretation of ancient texts. Its meaning has continually changed and has been dependent on one’s particular time and environment. Famed psychiatrist Carl Jung emphasized the psychological significance of this word:

“I cannot define for you what God is. I can only say that my work has proved empirically that the pattern of God exists in every man and that this pattern has at its disposal the greatest of all his energies for transformation and transfiguration of his natural being.”

Pantheists use God to describe natural laws because they often notice a mysterious order and oneness in our universe, as revealed by physics, mathematics, science, philosophy, as well as empirical evidence. Pantheists tend to believe that everything and every moment are part of a natural order. Cynics view nature as chaotic, but Einstein believed in unity and added,

“We believers in physics, know that the distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.”

The implication is that in the grand scheme of things, fundamental distinctions may be an illusion. They are the words we use to try to affect things and the words we use to try to make sense of our world. Spinoza said,

“If men were born free, they would, so long as they remained free, form no conception of good and evil.”

When everything is one, words – which by their nature make themselves distinct from other words – fail at trying to describe what this oneness really means. Any words or descriptions we use (including God) will be insufficient for describing or understanding everything. Thus, Einstein had a parable to answer what God means for a pantheist:

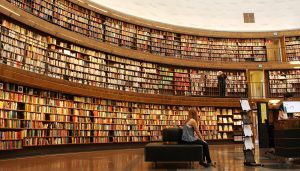

“The human mind, no matter how highly trained, cannot grasp the universe. We are in the position of a little child, entering a huge library whose walls are covered to the ceiling with books in many different tongues. The child knows that someone must have written those books. It does not know who or how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. The child notes a definite plan in the arrangement of the books, a mysterious order, which it does not comprehend, but only dimly suspects. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of the human mind, even the greatest and most cultured, toward God. We see a universe marvelously arranged, obeying certain laws, but we understand the laws only dimly. Our limited minds cannot grasp the mysterious force that sways the constellations.”

Pantheists are thus not quick to throw around the word God. However, when someone mentions it, a pantheist has an idea of what it means and what it does not mean. Carl Sagan explained his view of God in a similar way:

“The idea that God is an oversized white male with a flowing beard who sits in the sky and tallies the fall of every sparrow is ludicrous. But if by God one means the set of physical laws that govern the universe, then clearly there is such a God.”

What is revealed by science can be shrugged off as ordinary random realities of our universe, or they can be elevated to divine status. Divine language used to describe reality, amidst a planet full of weapons and misguided political and religious leaders, is an effective way to highlight and affirm our faith in this world. It’s a way for the adults in the room to speak to the children – and our own child inside – that the air we breathe is God, that every moment is God, and that life – including the pain it involves – is a blessing. This kind of positive faith is what has led to countless scientific discoveries and human advances. Einstein’s attempt at a unifying theory of relativity, for example, is still held today as being the most important equation of science. In regards to how such an important scientific breakthrough came to be, he said,

“I am of the opinion that all the finer speculations in the realm of science spring from a deeply religious feeling, and that without such feeling they would not be fruitful.”

Arguably the greatest breakthrough in science was inspired by the pantheistic perspective. Einstein even went further to suggest that the “fanatic” version of the atheistic perspective is inspired by psychological torment and religious child abuse. Indeed, some people become so deeply invested in arguing against God, that they become blind to a positive perspective. Atheism, ironically, accepts inferior ways of using the word God and related language. It thus allows immature people to hijack the word God. Agnosticism, in turn, leaves open possibilities of God and is a more popular view among many of our greatest thinkers. Pantheism takes a step forward and offers the directly abstract version of God that many of our finest thinkers of all persuasions lean toward. When everything is God, we know we will likely never understand “everything” and we will therefore never fully understand “God”. God represents the deepest feelings and reverence for the mysterious structure of the world as far as science can reveal it. As Ralph Waldo Emerson states,

“Every man is a divinity in disguise, a god playing the fool.”

So, the next time someone knocks at your door and wants to tell you about God, tell them that everything is God. Or, perhaps tell them what Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe said,

“If God had wanted me otherwise, He would have created me otherwise.”

Their church teases them with an infinite idea of God but then reduces “Him” to a controlling madman. The pantheist God is natural laws and a kind of perfection, reminding us that we are a part of this world and part of its destiny. We are wired for survival to pretend to have control in order to better ourselves, but everything – God – is what ultimately sways the constellations. The phrase, “I don’t believe in God”, just reinforces old beliefs and may even limit and demote one’s own divine relationship with cause and effect, natural laws, and the order and harmony of the world as far as science can reveal it. Einstein:

“In view of such harmony in the cosmos which I, with my limited human mind, am able to recognize, there are yet people who say there is no God. But what really makes me angry is that they quote me for the support of such views.”

The pantheist God isn’t necessarily worshipped, supernatural, or metaphysical. The distinctions between these words and their opposites are not even significant for a pantheist. All our distinctions are human constructs. It’s a world full of mystery, with evidence of oneness of our perceived distinctions, and which has no anthropomorphic character as far as science is concerned. One way to consider it: the word God represents this mysterious oneness, whereas just calling it “universe” or “energy” or whatever else tends to suggest pockets of emptiness and chaos (or worse, the smug suggestion that everything has been figured out). Carl Jung asks and answers:

“But why should you call this something ‘God’? I would ask: ‘Why not? It has always been called ‘God.’”

Pantheism’s use of God signifies gratefulness and awe for the signs of unity which inspire love for this world and also inspire amazing human achievement. That’s why some of us call pantheism: the advanced definition of God.

“We are in the position of a little child, entering a huge library whose walls are covered to the ceiling with books in many different tongues… The child notes a definite plan in the arrangement of the books, a mysterious order, which it does not comprehend, but only dimly suspects. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of the human mind, even the greatest and most cultured, toward God.” -A. Einstein