“I don’t know why we are here, but I’m pretty sure that it is not in order to enjoy ourselves.”

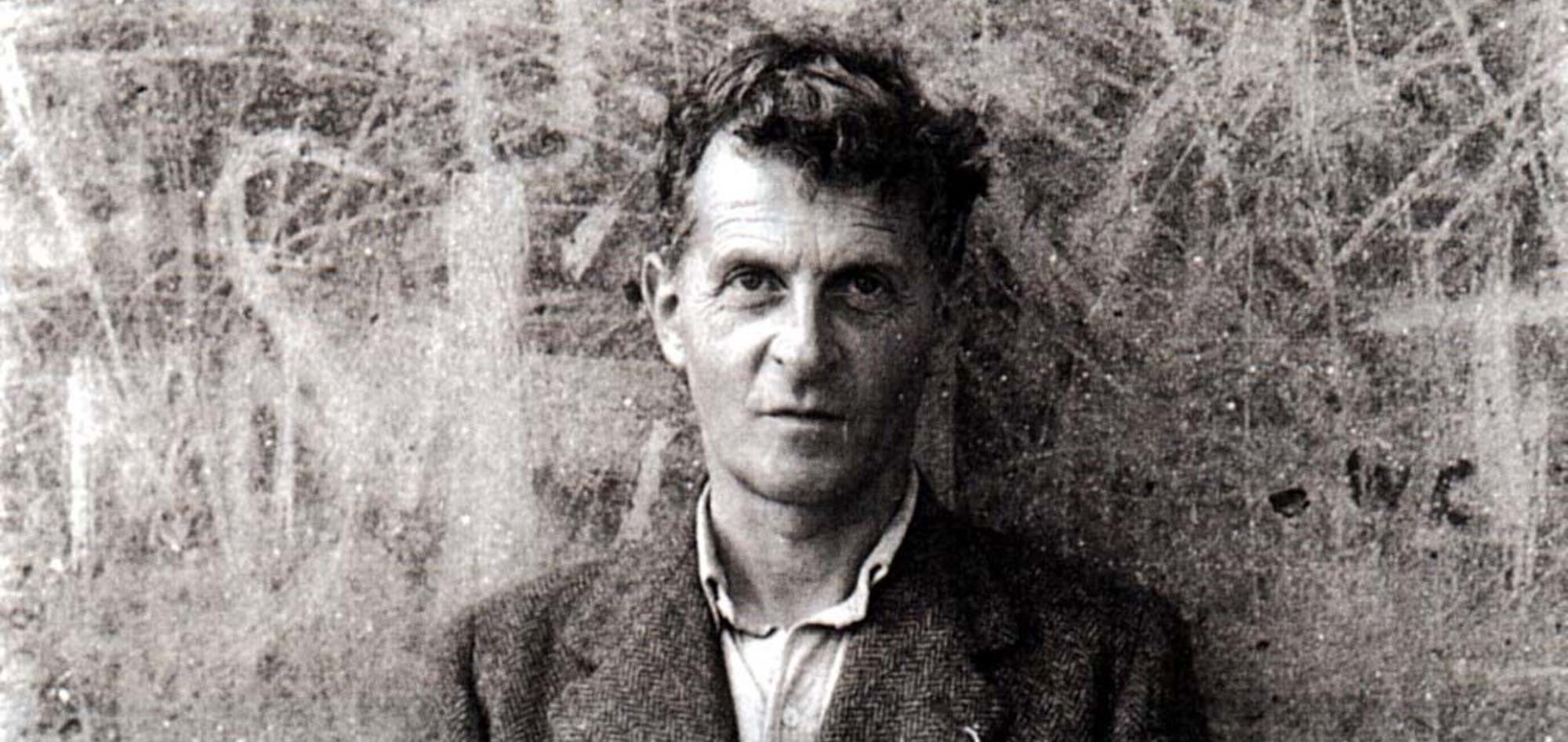

He was the home-schooled child of a super wealthy family with a strict and perfectionist father. Three of his brothers eventually killed themselves. He published only one book which he himself later rejected in his life.

“Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life.”

He was an often depressed, even suicidal, sometimes religious, bisexual man, who turned out to be a war hero and prisoner-of-war. He gave away much of his wealth and took on a modest schoolteacher job, but was still an unsettled man, taking out his frustrations by hitting the bad students.

“Hell isn’t other people. Hell is yourself.”

How did oddball Ludwig Wittgenstein become the most influential philosopher of the 20th Century?

His only published work was the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Philosopher G. E. Moore points out that the work’s Latin title was in honor of the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus by Baruch Spinoza. Wittgenstein stated in his Tractatus,

“Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

And that was a main theme in his work. That philosophy is limited by words:

“The limits of my language means the limits of my world.”

For him, language was the key to understanding where our ideas come from:

“To imagine a language is to imagine a form of life.”

It is life that naturally leads us to more questions, which lead us to trying to answer the unanswerable:

“Man feels the urge to run up against the limits of language. Think for example of the astonishment that anything at all exists. This astonishment cannot be expressed in the form of a question, and there is also no answer whatsoever. Anything we might say is a priori bound to be nonsense. Nevertheless we do run up against the limits of language. Kierkegaard too saw that there is this running up against something, and he referred to it in a fairly similar way (as running up against paradox). This running up against the limits of language is ethics.”

Philosophy ultimately leads to nonsense, for Wittgenstein:

“A serious and good philosophical work could be written consisting entirely of jokes.”

He further points out the absurdity of philosophy in his notes entitled, “On Certainty”:

“I am sitting with a philosopher in the garden; he says again and again ‘I know that that’s a tree’, pointing to a tree that is near us. Someone else arrives and hears this, and I tell him: ‘This fellow isn’t insane. We are only doing philosophy.”

For Ludwig, it isn’t just philosophy that’s limited but also scientific belief:

“At the core of all well-founded belief lies belief that is unfounded.”

Science, a most well-founded belief, simply cannot answer our biggest questions:

“We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have still not been touched at all.”

Instead the truest touch of reality lies somewhere in a realm of the unknowable:

“We are asleep. Our Life is a dream. But we wake up sometimes, just enough to know that we are dreaming.”

This kind of thinking takes philosophy into a more spiritual dimension:

“The mystical is not how the world is, but that it is.”

Wittgenstein defines his mystical idea of God like other pantheists:

“How things stand, is God. God is, how things stand.”

God is not a limited idea:

“To believe in God means to see that the facts of the world are not the end of the matter.”

Like Einstein, Spinoza, and other pantheists, Wittgenstein questions time and the idea of “death”:

“Death is not an event in life: we do not live to experience death. If we take eternity to mean not infinite temporal duration but timelessness, then eternal life belongs to those who live in the present. Our life has no end in the way in which our visual field has no limits.”

He is not impressed with the focus of what happens “after” death:

“The real question of life after death isn’t whether or not it exists, but even if it does what problem this really solves.”

Wittgenstein in his notes later in his life searched for things that must be exempt from doubt, seemingly contradicting or at least amending his skepticism of philosophy altogether. His way of thinking and continued private search for truth may have been a reflection of a person who led a particularly diverse and interesting life.

“Nothing is so difficult as not deceiving oneself.”