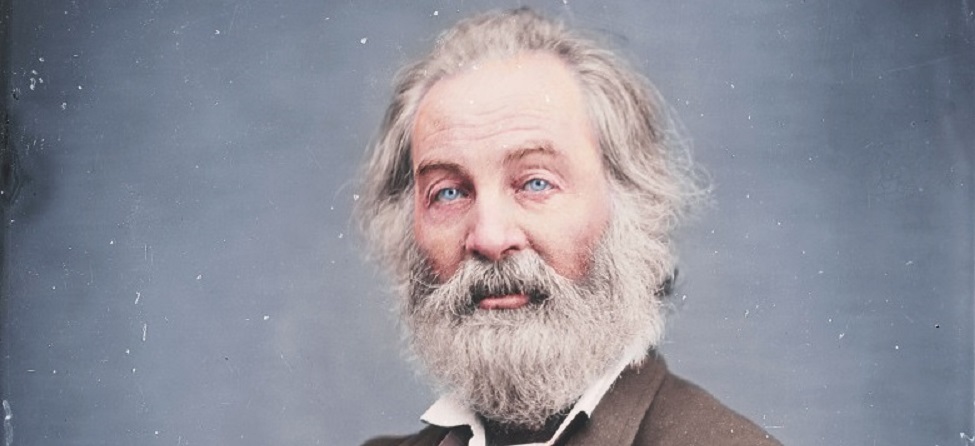

Walter “Walt” Whitman (1819 – 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist. He wrote in the period surrounding the American Civil War, incorporating the popular philosophies of both transcendentalism and realism in his works. Whitman is considered one of most influential American poets of all time, often called “the father of free verse.” His work generated significant controversy in its day, particularly some of the poems in his anthology ‘Leaves of Grass.’ Although the book was denounced as obscene for its overt sexuality, Walt characteristically voiced defiance to such criticism.

A line from ‘Leaves of Grass’ (Section 51 of ‘Song of Myself’) is indicative of his contempt: Responding to his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson’s poetry (“A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines…Speak what you think now in hard words, and to-morrow speak what to-morrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict every thing you said to-day. To be great is to be misunderstood.”), Whitman shrugged off his critics’ small-minded orthodoxy in three short lines:

“Do I contradict myself?

Very well, then, I contradict myself;

I am large — I contain multitudes.”

After the first edition of Leaves of Grass was published in 1855, Whitman spent most of his professional life writing and re-writing it, revising it nine times until his death. Beginning as a book of twelve poems, his “deathbed edition” contained a compilation of over 400. Although panned by many critics as “pretentious” and “a mass of stupid filth,” it is clear Whitman did not take himself too seriously: The title ‘Leaves of Grass’ was a pun, with “Grass” being a term given by publishers to works of minor value, and “leaves” being another name for the pages on which they were printed.

Whitman epitomized the artist who suffered for his work. He was fired from his job at the Department of the Interior after devout Methodist and Secretary of the Interior James Harlan found ‘Leaves of Grass’ offensive. Critic Rufus Wilmot Griswold reviewed ‘Leaves of Grass’ and categorized Whitman as a ‘filthy free lover.’ Griswold suggested (in Latin) that Whitman was guilty of “that horrible sin not to be mentioned among Christians,” insinuating Whitman’s homosexuality. Unfazed, Whitman inserted the full review, including the innuendo, in a later edition of Leaves of Grass. Still, Griswold’s review proved caustic, almost suspending the publication of the second edition. Whitman’s first publisher refused to republish the book based on the reviews, instead returning the plates to Whitman when suggested changes and deletions were ignored. The setback was temporary, however: Whitman found a new publisher, Rees Welsh & Company, which released the second edition in 1882.

Whitman predicted the controversy would increase sales, and it did. The first printing of the second release sold out in a day. The book eventually found a much wider audience, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, who was so impressed that he wrote a flattering five-page letter to Whitman and shared the work among his friends. Today, ‘Leaves of Grass’ is considered one of the most important anthologies in American history.

The poems of Leaves of Grass are loosely connected, with each representing Whitman’s celebration of life and humanity. The book is notable for its discussion of sensual pleasures during a time when such candid displays (such as this stanza dedicated to oral sex) were considered immoral:

“Loafe with me on the grass, loose the stop from your throat, / … Only the lull I like, the hum of your valved voice.” ~ Walt Whitman, ‘Song of Myself’

Influenced by Emerson and the Transcendentalist movement, Whitman’s poetry praised nature and the individual human’s role in it. True to transcendentalism, Whitman never diminished the role of the mind or the spirit, but rather elevated human passions, deeming all worthy of poetic praise:

“This is what you shall do; Love the earth and sun and the animals, despise riches, give alms to every one that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God, have patience and indulgence toward the people, take off your hat to nothing known or unknown or to any man or number of men, go freely with powerful uneducated persons and with the young and with the mothers of families, read these leaves in the open air every season of every year of your life, re-examine all you have been told at school or church or in any book, dismiss whatever insults your own soul, and your very flesh shall be a great poem and have the richest fluency not only in its words but in the silent lines of its lips and face and between the lashes of your eyes and in every motion and joint of your body.”

Although Whitman proclaimed respect for all religions, his skepticism kept him from attending any services. His pantheism, however, was evident in many of his writings:

“The soul or spirit transmits itself into all matter.”

“I have said that the soul is not more than the body,

And I have said that the body is not more than the soul,

And nothing, not God, is greater to one than one’s self is”

He frequently argued for a monistic view of life, and a refutation of duality, as in this stanza on death:

“The smallest sprout shows there is really no death;

And if ever there was, it led forward life, and does not wait at the end to arrest it,

And ceas’d the moment life appear’d.

All goes onward and outward—nothing collapses;

And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.”

American Philosophy: An Encyclopedia qualifies Whitman as a man who “took a more pantheist or pandeist approach, by rejecting views of God as separate from the world.” But surely the most telling view of Whitman’s spirituality lies in his own words, excerpted here from ‘Poem of Perfect Miracles’:

“To me, every hour of the light and dark is a miracle,

Every inch of space is a miracle,

Every square yard of the surface of the earth is spread with the same,

Every cubic foot of the interior swarms with the same;

Every spear of grass—the frames, limbs, organs,

of men and women, and all that concerns them,

All these to me are unspeakably perfect miracles.”

~ Walt Whitman