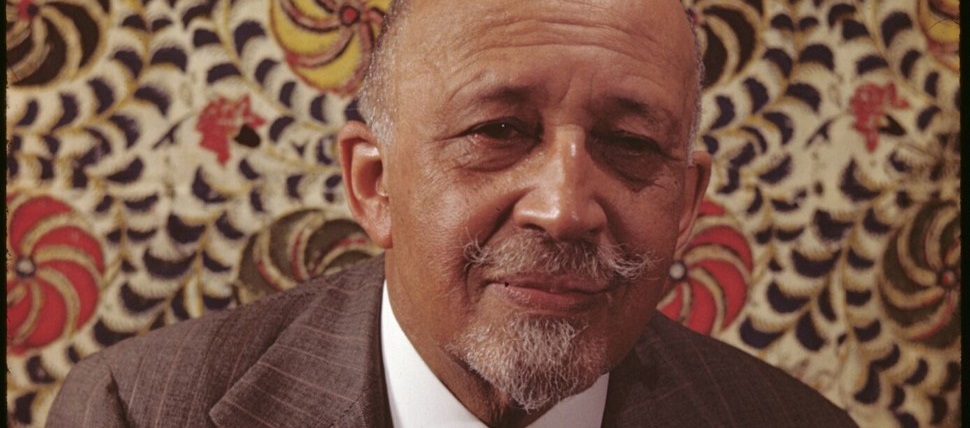

William Edward Burghardt (W.E.B.) Du Bois (1868 – 1963) was a pioneering American sociologist, Pan-Africanist, civil rights activist and organizer, and author. Born in the partially-integrated community of Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois (pronounced “Due Boyce”) grew up relatively peacefully, raised by a single mother and attending a Congregational church. He studied at Fisk University, earned a Ph.D. at Harvard in 1895 — the first African American to do so — and did further graduate work at the University of Berlin.

In July 1897, he became a professor of history, sociology and economics at Atlanta University. It was there that Du Bois first witnessed virulent racism. Forty years after Emancipation, lynching mobs and malignant hatred against blacks were still commonplace in the South. Du Bois described this racism as a “great, red monster of cruel oppression,” and vowed to use his intellectual strength and the power of the black church to combat it.

In 1903, Du Bois published one of the most powerful and influential books in American history, The Souls of Black Folk. Borrowing a phrase from Frederick Douglass, Du Bois began his collection of 14 essays with the poignant term ‘color-line,’ a reference to the injustice of the ‘separate but equal’ doctrine then prevalent in American social and political life:

“The problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color-line — the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.”

Each chapter of the book begins with two epigraphs – one from a white poet, and one from a black spiritualist. In doing so, Du Bois sought to highlight the intellectual and cultural parity of black and white cultures. A major theme of his work was the double-identity faced by African Americans: being both American and black. Du Bois argued that although this dual consciousness had been a handicap in the past, it could be a strength in the future.

Du Bois continued to release numerous studies dealing with the issues and problems that faced black Americans while at Atlanta University, but became impatient with academia over time. Frustrated with what he felt was a lack of progress, he began touring the country, giving lectures and advocating for protest. By 1906, Du Bois had achieved national prominence as the leader of the Niagara Movement, a group of African-American activists seeking equal rights for blacks. Du Bois and his supporters were particularly opposed to an agreement crafted by Booker T. Washington called the ‘Atlanta Compromise.’ Washington’s accommodationist policy stated that Southern blacks would work and submit to white political rule in return for basic educational and economic opportunities. Du Bois rejected this proposal, insisting that blacks be given full civil rights and increased political representation. He believed this would be brought about by the African-American intellectual elite he called ‘the Talented Tenth.’

Du Bois resigned from Atlanta University in 1910 to help found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), where he acted as Director of Publicity and Research, and Editor of its influential journal, The Crisis. He traveled frequently to Africa and Russia in this role. As time passed, Du Bois’ politics began to lean to the far left. By 1961, he had joined the Communist Party and left the United States for Ghana. His health declined there, and he died on August 27, 1963, in the capital of Accra. The following day, at the March on Washington made famous by Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, speaker Roy Wilkins asked the hundreds of thousands of marchers to honor Du Bois with a moment of silence. Just one year later, The Civil Rights Act of 1964, embodying many of the reforms Du Bois had campaigned for his entire life, was signed into law.

Throughout his life, Du Bois argued for the black church to become involved in the fight for civil rights. He was not personally religious as an adult, however. After attending a New England Congregational church as a child, he abandoned organized religion while at Fisk College. Du Bois preferred the term freethinker, evident in this rejection to lead a public prayer:

“When I became head of a department at Atlanta, the engagement was held up because again I balked at leading in prayer … I flatly refused again to join any church or sign any church creed. … I think the greatest gift of the Soviet Union to modern civilization was the dethronement of the clergy and the refusal to let religion be taught in the public schools.”

That said, Du Bois did openly acknowledge a belief in God:

“I believe in God, who made of one blood all nations that on earth do dwell. I believe that all men, black and brown and white, are brothers, varying through time and opportunity, in form and gift and feature, but differing in no essential particular, and alike in soul and the possibility of infinite development.”

This statement must be nuanced by his other comments, however. His interpretation of God appears to be pantheistic. In ‘A Political Companion to W. E. B. Du Bois,’ Nick Bromell wrote:

“(W.E.B. Du Bois’ religious view) was at least a Vedic-resonant view. For example, at the conclusion of his book Darkwater, Du Bois offers a poem, “A Hymn to the Peoples,” in which he beseeches a “World Spirit,” a “Human God,” to make “Humanity Divine.” Clearly, his invocation of such a permeating divinity places Du Bois in the general camp of pantheism or panentheism. And in the novel Dark Princess, Du Bois, using the mouthpiece of Kautilya, speaks of a spark of divinity in human beings that is continually reincarnated and claims, “We are eternal because we are God.” As we will see later, Du Bois often uses the character Kautilya to present his more considered views.”

Du Bois own words about his religious views are particularly enlightening. In a 1948 letter to the Cuban Baptist minister E. Pina Moren, Du Bois answered Moren’s question, “I would like to know if you are a believer in God; also what is your opinion about the Lord Jesus?”:

“If by being ‘a believer in God,’ you mean a belief in a person or vast power who consciously rules the universe for the good of mankind, I answer No; I cannot disprove this assumption, but I certainly see no proof to sustain such a belief, neither in History nor in personal experience. If on the other hand you mean by ‘God’ a vague Force which in some incomprehensible way, dominates all life and change, then I answer Yes; I recognize such Force and if you wish to call it God, I do not object.” ~W.E.B. Du Bois